Everyday Africa - Chapter 1, Revisited

Before it became a network of photographers, a global movement, a book, an education program - before we could have imagined how far it would take us - Everyday Africa began as an exercise in stripping away a preconceived narrative.

Austin Merrill and I were traveling in Ivory Coast in March 2012, as a writer / photographer team covering the continued strife a year after the country’s post-election violence and the cocoa trade that is, in part, the root of turmoil there. Austin is intimately familiar with the country, having lived there at a couple different points in his life, and I had been there before as a photojournalist, and had lived several years “next-door” in Ghana. During the March 2012 trip we began making photos on our phones, very casually, and it occurred to us that those images felt much more familiar to us than the ones I was “professionally” making for the story we were there to tell.

Having outlined that story above – as you can imagine, it was a bit predetermined. I think often about the process of photojournalism – going into a story, you often feel you “know” the images needed to tell it. If it’s a story with phrases like “continued ethnic violence,” you feel you need photos of refugees, burned down homes, survivors with horrific stories to tell, etc. These are the images that will make sense to the readers, that they will find palatable. But along the way, we also see a lot of daily-life moments, and we often pre-edit these out of our story by not even photographing them. Austin and I decided to photograph them.

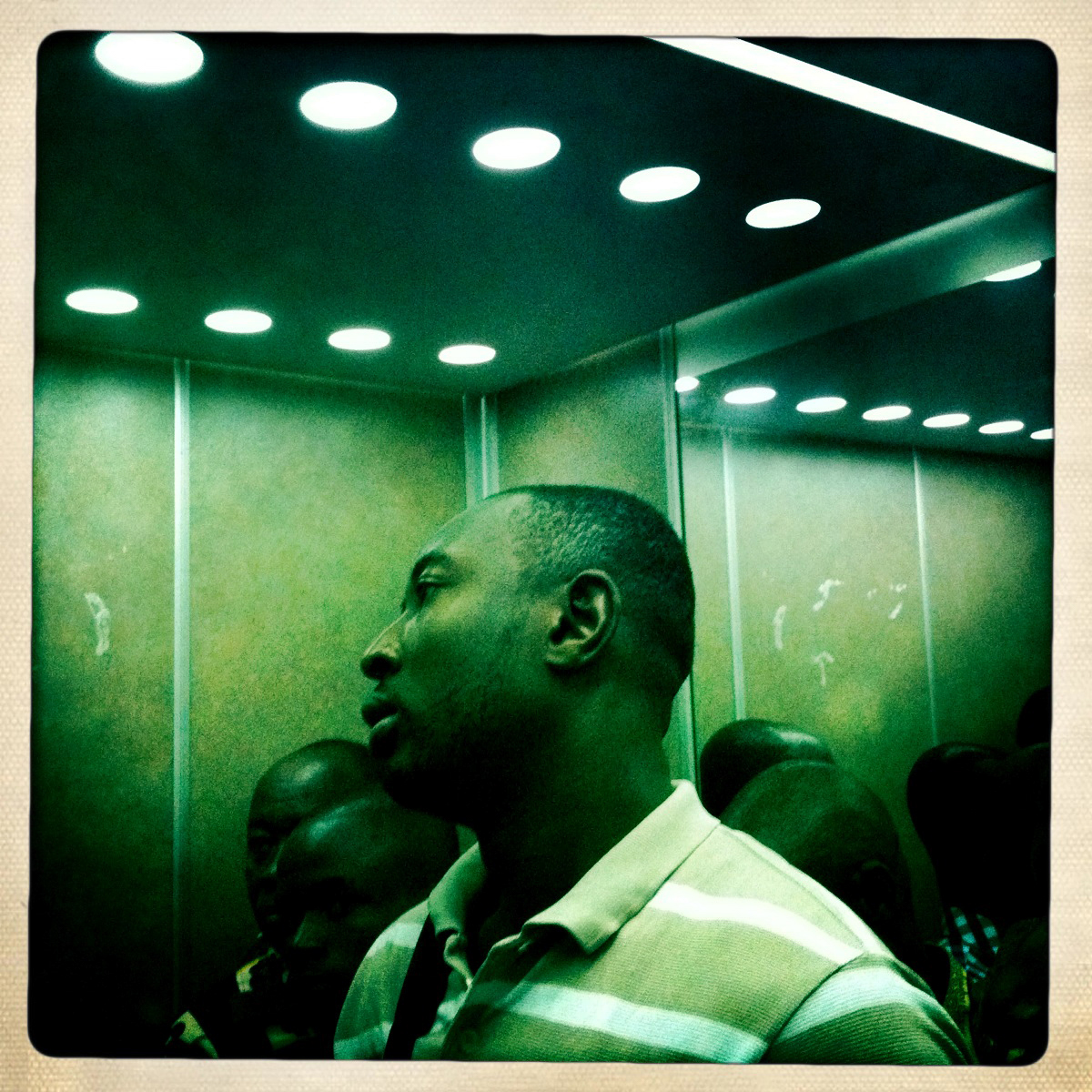

This is what a reporting trip looks like in chronological order. Unlike most photo stories, this one starts at the beginning and ends at the end. It starts with us in an elevator in a government building on the way to get our press passes just after we arrived, and it ends with us checking in for our flight at the airport as we were leaving exactly two weeks later. What happened in between happened in between.

In schools, we show a simplified version of this work. We have 35 minutes to tell our story, so we show the most obvious contrasts and comparisons: I can photograph refugees looking sad or photograph them buying DVDs. I can photograph destroyed homes while Austin photographs the hip young music fan in his clean Adidas shirt.

Daily life in the Conflict Story meant dealing in the lazy metaphors of our trade. A scene-setting image of smoke billowing in the air makes us imagine a burning village, but in reality the smoke is caused by the controlled burning of farmland to prepare for next year’s bounty. A dead, bloody pig for the Story, and in the same village, a man wiping a boy's nose (because I was photographing the boy) for Everyday Africa. Was I a liar? No no, just trying to stress the severity of the issue. Was I a liar? Maybe. If I was, am, then I think so many of us are.

Some of the discrepancies take a closer look. Subconscious decisions that are revealing in that they are subconscious. Why is the man lying in the rubber plantation checking his phone in the Everyday Africa photo, but facedown, as if napping or dead, in the Story? And why did I photograph such furtive, suspicious expressions on the faces of the men looking after the cocoa beans? What did they ever do to me?

It is not clean. It should not be clean. We try to make simple truths and arrange them into tidy stories. But ultimately the "truth" is based on how we feel about the situation.

But my mood changes all the time. Doesn't yours? Perhaps our moments should be less decisive.

The photographs below are by me and by Austin Merrill. Many thanks to the Pulitzer Center for sending us on that first trip and for all of their support since.